Quick Links - Saint Sarkis Armenian Apostolic Church

Social media

Contact information

Address

19300 Ford Road

Dearborn, MI 48128 - United States

Phone

(313) 336-6200

Fax

(313) 336-4530

It is generally agreed that the Armenian Church is the first one that has been officially recognized by the civil authorities of the country in which that particular Church existed. Yet, many people do not agree with the premise that the Armenian Church is apostolic, that is that she has been founded by an apostle of Jesus Christ. Such people like to call the Armenian Church Gregorian, thus implying that the Church originated only from the time of St. Gregory the Illuminator, who, they claim, was the first apostle of Armenia but who was certainly not one of the original apostles of Jesus, since his mission dates from about 300 A.D.

It is generally agreed that the Armenian Church is the first one that has been officially recognized by the civil authorities of the country in which that particular Church existed. Yet, many people do not agree with the premise that the Armenian Church is apostolic, that is that she has been founded by an apostle of Jesus Christ. Such people like to call the Armenian Church Gregorian, thus implying that the Church originated only from the time of St. Gregory the Illuminator, who, they claim, was the first apostle of Armenia but who was certainly not one of the original apostles of Jesus, since his mission dates from about 300 A.D.

The Armenians, on the other hand, maintain that Christianity was preached in Armenia first by the Apostles Thaddaeus and Bartholomew.

There is no extant Armenian documents of any kind dating from the era in question; therefore there could not have been any pertaining to the religious aspect of Armenian history of that period. However, the Armenian tradition about the apostolic mission is very strong and firmly rooted in order not to have an historic foundation. It is a well known fact in historiography that all traditions are based on actual historical facts, even though they may present these facts in a distorted form and out of true proportions. For example, there is no actual documentary proof that the Church of Rome was founded by St. Peter, but is based largely on tradition and on the say-so of later leaders of the Church.

The existence of a Christian Church in Armenia during the first centuries of our era has been proven; there have been persecutions of Christians during those centuries just as in the Roman empire. There could not have been persecutions of Christians if there were no Christians; and if there were Christians to be persecuted, it stands to reason to think that somebody preached to them the new religion which was absolutely foreign and unknown to the natives of Armenia.

The Armenian Apostolic Church is a branch and an integral part of the Universal Christian Church. Until the Council of Chalcedon (451 A.D.) the Christian Church was one. To set the dogmas of this one universal church, and to free it from the heretical nations infesting it in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, three Ecumenical Councils were convened: Nicea in 324, Constantinople in 381 and Ephesus in 431. In these three Councils the Fathers of the Christian Church formulated the orthodox interpretations of the Trinitarian doctrine, the incarnation and the two natures of Jesus Christ, the position of Virgin Mary as theotokes (God bearing) and all other theological points. In these three Councils the theology of the Christian religion was formulated for general usage in a concise form (Nicene Creed). Furthermore, in the last of these three councils it was solemnly declared that any further change, addition or deletion from the Creed or the accepted dogmas should be considered heresy.

The Armenian Apostolic Church accepted and has since strongly adhered to these dogmas and has never deviated from the doctrine set forth in the first three ecumenical councils. Other Churches have seen fit to call additional Councils, not for the purpose alone of settling minor points of canon law or ceremonial form, but for the further interpretation of basic theological points of the Christian religion. The changes suggested and accepted in these additional Councils have not been accepted by the Armenian Apostolic Church which has faithfully and firmly stood on the teachings of the first three councils, as have other Churches, namely the Oriental Orthodox churches.

After being founded by Sts. Thaddeus and Bartholomew in the first century, Christianity existed in Armenia continuously, even though in hiding, until the time of King Tiridates 1II who reigned between 287-330.

though in hiding, until the time of King Tiridates 1II who reigned between 287-330.

Since there was no Armenian literature prior to 406, all church services and the reading of the Scriptures were made in Syriac, and a translator used to interpret the lectures. At the time of Tiridates III, St. Gregory the llluminator came to Armenia from Caesaria, a great center of Greek Christianity in Cappadocia.

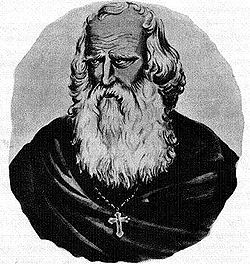

St. Gregory began to preach to Gospel openly; this incurred the wrath of the King, who after trying in vain to stop him, jailed him in a dungeon. Some years later when Tiridates became sick, his sister Khosrovidought, who had secretly joined the Christian religion, convinced him that he was being punished for the persecution of Christians and insisted that only Gregory could cure the King's sickness.

After St. Gregory was freed and brought to the Palace, he prescribed a seven days' fast and a true repentance. The King was cured, he accepted Christianity and decreed that henceforth in Armenia paganism shall be suppressed and Christianity shall be the state religion of the land. This event took place in the year 301.

St. Gregory became the first official head of the Armenian Church. In the early Church the bishops could be married and the succession of the Catholicate was hereditary. The two sons of St. Gregory, St. Aristakes and St. Verthanes, the sons of this latter St. Yousik, then Yousik's grandson St. Nersess and his son St. Sahag occupied the Catholical throne in turn.

The first Ecumenical Council of Nicea was called by Constantine the Great in 324; the official Armenian representative was St. Aristakes. In this Council, as mentioned earlier, the Creed was formulated in which is confessed the true Godship of Jesus Christ. In this Council it was also established the manner of determining the date of Easter, which before that time was arbitrarily observed. It was St. Nersess (Catholicos 348-374) who for the first time established in Armenia humanitarian institutions, such as hospitals, old age homes, orphanages, special camps for lepers, etc. He also organized religious celibate brotherhood and sisterhood, which were to become later the nuclei of the many monasteries in the country.

It was St. Nersess (Catholicos 348-374) who for the first time established in Armenia humanitarian institutions, such as hospitals, old age homes, orphanages, special camps for lepers, etc. He also organized religious celibate brotherhood and sisterhood, which were to become later the nuclei of the many monasteries in the country.

The need to keep the Armenian Church free of foreign influence was acutely felt towards the end of the 4th century; at this time the decline of the Arsacid Kingdom began and the political division of the country between the Byzantine Empire and that of Persia became a fact. To this need was added the necessity to conduct the church services in the native language.

It was St. Mesrob Mashtots who first thought of doing something about this situation which eventually led to his development of the Armenian alphabet. The written work in Armenian played a big role not only in making the Gospel understood by the general public without the help of an interpreter, but also gave to it a sense of self respect and a feeling of national identity and let to the opening of many schools and the translation of the Bible and other theological books.

A long line of Catholical succession through the following centuries forms the history of the Armenian Church; in this period the Armenians had to fight many a religious war against incomparably stronger foreign forces that were trying to convert them first to Persian Mazdeism (the war of Vartanantz) and later to Arab Mohammedanism.

With the rise of the Bagratid dynasty (855) the Church also had a chance to prosper; in this period many new churches were built, monasteries reorganized, many manuscripts were written.

In the eleventh century Armenia was again politically disorganized. There was no central authority; foreign despots from one side and native regal and feudal princes on the other, helped to divide the country in many parts. The Church also suffered with many schisms. At one time there were as many as 6 or 8 Cathololicoses. The legitimate Catholicos was Gregory II, surnamed The Martyrophile, (1065-1105). He went abroad for a long period of time and his absence did not help the matters at home.

At about this time unbearable conditions in Armenia forced many Armenians to migrate toward Cilicia, where more propitious conditions existed.

Catholicos Gregory III (113-1166) moved the Catholicate to the Black Mountains; a little later, Nersess the Gracious moved it to Hromkla (about 6 miles Northeast of Aintab); from this last place the Catholical chair was moved to Cilicia. This was the beginning of the Cilician See. Later on, when conditions were improved, a desire to repatriate the Catholicate was made known to the Catholicos Gregory IX Mousapegian (1439-1441). The Catholicos did not consent to this proposal, but he suggested to elect another Catholicos for the See of Etchmiadzin. This was done and Kisakes of Virap became the first Catholicos of Etchmiadzin of this second period. This is the beginning of the two Catholicate system which still prevails.

As soon as Mesrob developed the Armenian alphabet, a literary movement began in Armenia. The first object of this movement was the translation of the Bible and second the translation of the important works of Greek and Syrian Fathers. Among the translated works there are some whose Greek originals were later lost, and the Armenian translations took international meaning, for example the Chronicle of Eusebius.

During the initial period (406-440) the Armenian literature produced was exclusively translations. A second category of writers comprise those who have written panegyrics, of which there are quite a number. A third group of authors has specialized in history; these could be found mostly from the 7th to the 12th centuries.

Purely theological problems have been treated by such authorities as John the Philosopher, St. Nersess the Gracious, Gregory of Tadeu. These authors and some others have expounded the theology of the Armenian Church in detail.

Special mention should be made of Gregory of Narek, whose Book of Laments, known as Narek, has been, and even today is, considered unique in its kind, as the mystical expressions of a self-conscious soul.

From time to time there were some people in high standing in the Armenian Church, who, either for political or some other reason, saw advantage in a reunion with the Western Churches. A few of these people were willing to sacrifice some principles for the sake of unity, others wanted to achieve the same end by mutual understanding.

Such efforts were made by Catholicos Ezra (630-641) who negotiated with Emperor Heraclius.

In the time of the Catholicos Gregory Pahlavouni, again efforts were made for rapprochement with the Greek Church; the negotiations continued between Nersess the Gracious and Emperor Manual Comnenus, but could not be consummated on account of the deaths of the Catholicos and the Emperor, and the pressure exerted by the bishops and the vardapets of Eastern Armenia, who were against the union of the Armenian Church with any other.

During the crusades another movement was started, this time with the sanction, if not the deliberate instigation of the Rubinian Kings, who were the last reigning Armenian princes, having formed a new Armenia in Cappadocia and Cilicia. Although this movement also failed, some Armenian clerics again tried to accomplish the union with the Latin Church; these people, encouraged by Rome, went so far as to actually form a congregation after the style of the Dominican Order, and evangelized their doctrine among the Armenian population; these people were called unitors. They did not succeed in uniting the Armenian Church with Rome, but eventually caused a schism in the Church, creating the Armenian Catholic community.

The Armenian Church today is an autocephalous body, The Church is unique in that besides being a religious institution it is also a national institution inasmuch as almost all of its members are either Armenians or of Armenian descent, and for many centuries has played, in the absence of organized Armenian government, the role of this latter.

The hierarchical organization of the Armenian Church since 1441 recognizes two co-equal heads, each with the title of Catholicos. The primary Catholical See is in Etchmiadzin, Armenia, the seat of the Catholicos of All Armenians; The second is in Antelias, Lebanon, the seat of the Catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia. Each of these two Sees has its own dioceses, which are usually under the supervision of an Archbishop or a Bishop. The Armenian Church has two patriarchs, the first of which resides in Jerusalem and the second in Istanbul (Constantinople). Both patriarchs are spiritually dependent of the Etchmiadzin See, although they have fiscal and organizational independence.